“But today I see more clearly than yesterday that back of the problem of race and color lies a greater problem and that is the fact that so many civilized person’s are willing to live in comfort even if the price of this is poverty, ignorance, and disease of the majority of their fellowmen, [and] that to maintain this privilege men have waged war until today war tends to become universal and continuous.”

Known for his intellectual legacy and relentless, uncompromising activism, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois lived an extraordinary life. Although W.E.B. Du Bois was raised in an integrated community, unlike most Black people during this time, Du Bois was interested in studying race. W.E.B. Du Bois experienced his first encounter with racism as a student at Fisk University, where he attended until 1888 - graduating as a junior and enrolling in Harvard. And further experienced the malicious violence against Black people in the South while teaching at Atlanta University.

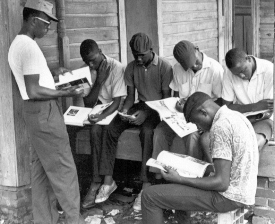

By 1895 Du Bois earned an education that very few people of any race had. He completed his Bachelors, then his Masters and Doctorate degrees at Harvard, becoming the first Black person to attend Harvard and the first Black person to receive a Doctorate degree. During a time when many Black people were pursuing higher social status by appealing to the principles of whites, Du Bois was known for his many unwavering writings and philosophies in regard to unconditional equality and civil rights of Black people in America. Being an advocate of higher education, Du Bois strongly believed that higher education was essential in the success of his people in this country.

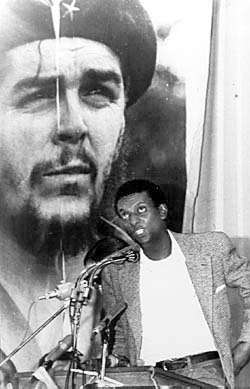

As a supporter of socialist principles, Du Bois analyzed capitalism’s role in maintaining poverty within the Black community in a number of his essays, and, as a result of his popularity and philosophies, came under immense examination by the U.S. government.

After being denied a passport to travel for eight years, Du Bois was finally able to travel overseas. During his travels, he visited a number of communist countries. While visiting China in 1959, Du Bois expressed his dismay with the United States by stating, “in my own country for nearly a century I have been nothing but a nigger.” In 1961 Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana, invited Du Bois to work on an Encyclopedia Africana. Moving to Accra, Ghana in 1961, Du Bois renounced his U.S. citizenship and remained there until his death in 1963.

It is important to recognize Du Bois’ unapologetic Black pride, and his work as he consistently strived for unconditional equality and rights for our people. He sought to empower Black people through education, culture and leadership and his legacy will continue to live on through those who fight today for Black liberation.

“One ever feels his twoness - an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Contributed by: Mariel Watkins